Osteoporosis Requires Individualized Screening and Management

Osteoporosis is a common medical condition that increases fracture risk and may require patients to make lifestyle changes.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease involving low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, resulting in increased bone fragility and fracture risk.1

Bone density corresponds to the amount of mineral within a volume, and bone quality depends on architecture, bone matrix composition, bone turnover, damage accumulation, and mineralization.2 Osteoporosis develops silently over years before it becomes apparent through bone mineral density (BMD) screening or fractures. Fragility fractures are the main physical manifestation and occur at diverse sites, such as the distal radius, proximal femur, and vertebral bodies.

Who Should be Screened?

Recommend a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to check BMD and screen for osteoporosis in the following patients at high risk3:

- Adults on chronic glucocorticoid therapy, such as oral prednisone ≥5 mg/day for 3 or more months or an equivalent

- Individuals aged 50 years and older with a recent low-trauma fracture

- Men aged 70 years and older

- Women aged 65 years and older

Other patients may also be good candidates for a DXA to check BMD, especially those with multiple risk factors. Assess risk factors to see if BMD testing is warranted with a thorough history in men aged 50 to 69 years or postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years with the following medical concerns3:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Excessive alcohol intake of 3 or more drinks per day

- Family history of fracture

- Fracture risk of 9.3% or greater per the fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX)

- History of delayed puberty

- Hyperparathyroidism or hyperthyroidism

- Hypogonadism

- Immobility or inactivity

- In menopausal transition

- Radiographic osteopenia (DXA T-score between -1 and -2.5)

- Repeated falls

- Smoking

- Taking medications that decrease BMD, such as aromatase inhibitors, glucocorticoids, GnRH agonists, phenobarbital, or phenytoin

Classification

There are 3 different categories of bone health for classification purposes:

- Normal bone health: BMD 1 standard deviation or less below that of young white women reference mean (ie, T-score of −1 or greater)

- Osteopenia: BMD between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations below that of young white women reference mean (ie, T-score between −1 and −2.5)

- Osteoporosis: BMD more than 2.5 standard deviations below that of young white women reference mean (ie, T-score less than −2.5)

Indications for Pharmacotherapy4

There are specific indications for pharmacotherapy:

- T-score of −2.5 or less (ie, or worse) in distal third of radius, femoral neck, spine, or total hip

- T-score from −1 down to −2.5 in distal third of radius, femoral neck, spine, or total hip, and fragility fracture of hip or spine

- T-score from −1 down to −2.5 in distal third of radius, femoral neck, spine, or total hip, and FRAX score shows that that 10-year probability of hip fracture is 3% or greater or the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture is 20% or more

Screening During Osteoporosis Treatment5

There are different approaches to screening. Some think that it is not necessary to check a DXA in patients who are receiving osteoporosis treatment because women receiving osteoporosis treatment may have reduced fractures, regardless of the impact on BMD. Others recommend continuing to check a DXA during treatment until BMD has stabilized or after 3 to 5 years of bisphosphonate therapy.

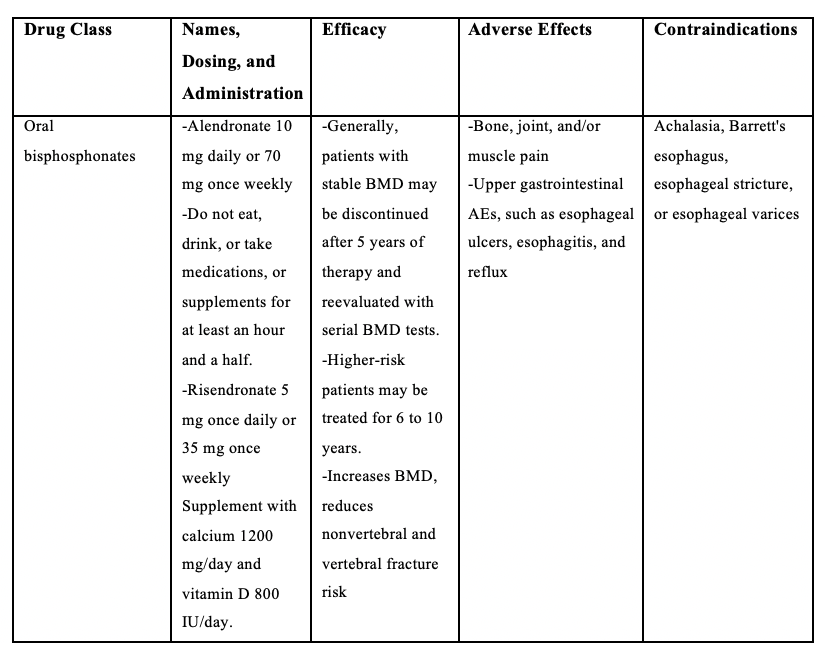

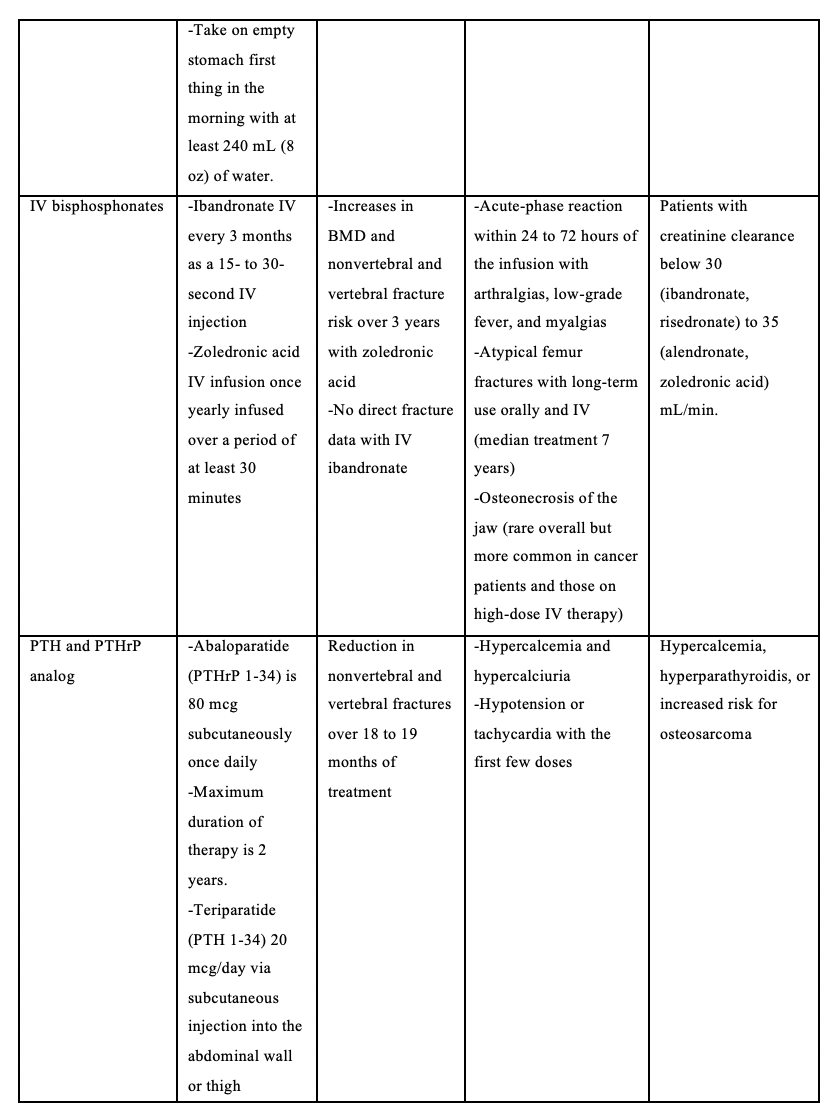

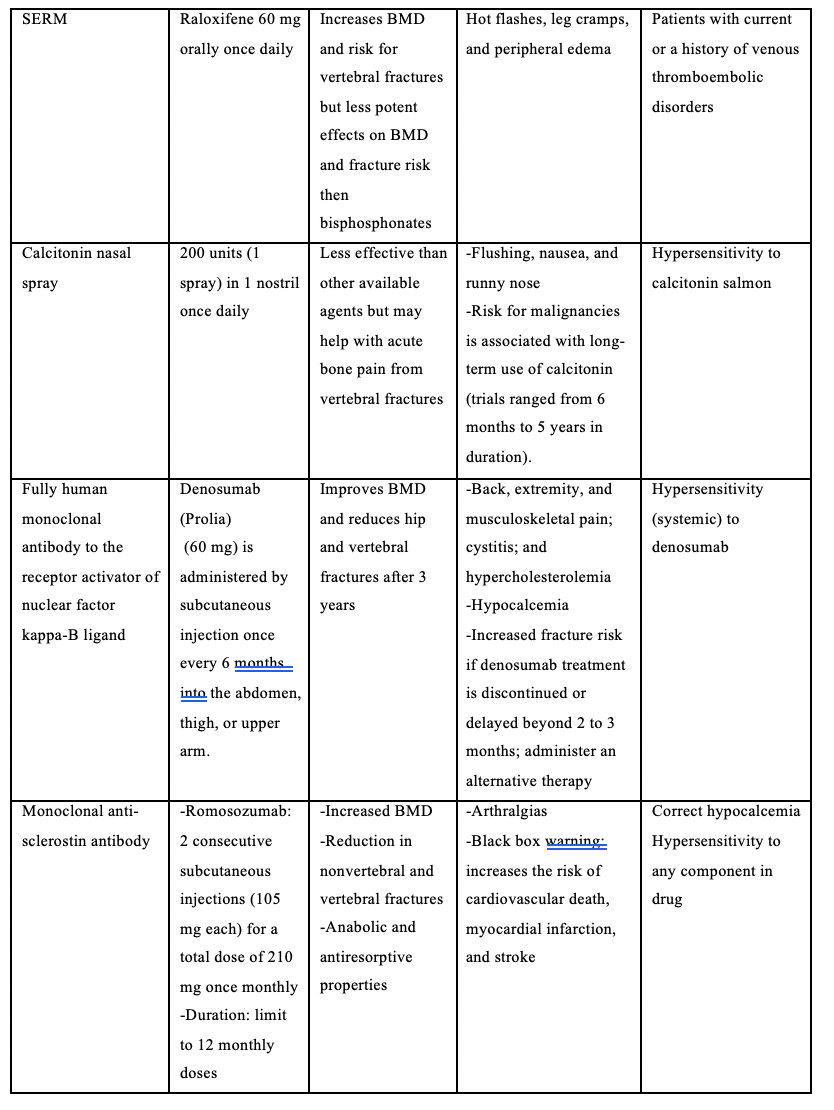

Medications for Osteoporosis

There are several pharmacotherapeutic options for osteoporosis treatment. Medications are classified mechanistically as antiresorptive agents that slow bone breakdown or anabolic “bone building” agents.

Antiresorptive medications include intravenous (IV) and oral bisphosphonates; selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), specifically raloxifene and calcitonin nasal spray; and subcutaneous denosumab. Romosozumab-aqqg is a subcutaneously administered monoclonal antibody with anabolic/antiresorptive properties.

Anabolic agents are the subcutaneous parathyroid hormone analogs abaloparatide and teriparatide. Oral bisphosphonates, such as alendronate or risendronate, are generally preferred first-line agents for osteoporosis prevention and treatment in most patients. The choice of osteoporosis medication depends on multiple factors, including cost, osteoporosis fracture risk and severity, route of administration, and tolerability. The Table4,6-11 details the adverse effects (AEs), contraindications, and dosing of osteoporosis medications.

There are specific circumstances for which other osteoporosis medications may be considered.Raloxifene may be an option for women at high risk for breast cancer and in women who cannot tolerate bisphosphonates or denosumab.4,8 Calcitonin may be an option to reduce acute bone pain associated with vertebral fractures as well.

Patients with severe osteoporosis and very high fracture risk who cannot tolerate or respond poorly to IV and oral bisphosphonates may be candidates for anabolic agents abaloparatide or teriparatide or alternatively romosomuzab.8-10 Denosumab is an alternative to anabolic agents for high-risk older patients who cannot take or tolerate or respond poorly to bisphosphonates.12

Table. Osteoporosis Medications4,6-11

AE indicates adverse effect; BMD, bone mineral density; IV, intravenous; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; and SERM, selective estrogen receptor modulator.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a common medical condition that increases fracture risk and requires individualized screening and management. Lifestyle management includes adequate vitamin D and calcium intake, increased physical activity, and smoking cessation. Oral bisphosphonates are first line for most patients with osteoporosis. Other agents may be reserved for high-risk patients who are intolerant or poorly responsive to bisphosphonates. Follow-up BMD testing is recommended to monitor response to therapy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jennifer Hofmann, DMSc, MS, PA-C, is a clinical associate professor at Pace University’s College of Health Professions in New York, New York.

Jean Covino, DHSc, MPA, PA-C, is a clinical professor at a department chairperson at Pace University’s College of Health Professions.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

REFERENCES

- Black DM, Rosen CJ. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(3):254-262. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1513724

- Chapurlat R Genant H. Osteoporosis. In: Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Jameson JL, De Groot L, eds. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2016;1184-213.e6.

- Allen S, Forney-Gorman A, Homan M, Kearns A, Kramlinger A, Sauer M. Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Updated July 2017. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://www.icsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Osteo.pdf

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, Denberg TD, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):818-839. doi:10.7326/M15-1361

- Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing Osteoporosis in Patients on Long-Term Bisphosphonate Treatment: Report of a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res.2016;31(1):16-35. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2708

- Silverman S, Christiansen C. Individualizing osteoporosis therapy. Osteoporosis Int. 2012;23(3):797-809. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1775-y

- Cranney A, Papaioannou A, Zytaruk N, et al. Parathyroid hormone for the treatment of osteoporosis: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2006;175(1):52-59. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050929

- Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1532-1543. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607948

- Forteo [prescribing information]. Indianapolis, IN; Lilly USA: 2020. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021318s053lbl.pdf

- Ringe JD, Doherty JG. Absolute risk reduction in osteoporosis: assessing treatment efficacy by number needed to treat. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(7):863-869. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-1311-y

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):756-765. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809493