Identifying Important Antidiabetic Drug–Drug Interactions

Clinicians can do 3 easy things when caring for diabetic patients to prevent drug interactions: implement medication reconciliation into daily practice, understand how drugs interact with each other, and know high-risk antidiabetic drug–drug combinations.

Diabetic patients represent 9.3% of the US population.1Most adults with diabetes have at least one comorbidity, such as depression, arthritis, heart disease, high low density-lipoprotein cholesterol, or high blood pressure.2Patients may take an average of 4 to 5 medications daily for their diabetes and comorbidities, excluding OTC medications, vitamins, and minerals.3Each additional medication increases the risk of potential problems, including drug—drug interactions.

Clinicians can do 3 easy things when caring for diabetic patients to prevent drug interactions: (1) implement medication reconciliation into daily practice, (2) understand how drugs interact with each other, and (3) know high-risk antidiabetic drug­—drug combinations.

Medication Reconciliation

A small yet important part of any patient encounter is a complete medication reconciliation, the process of identifying the most accurate list of all medications a patient takes.4Having a comprehensive list allows clinicians to provide quality care, make accurate recommendations, and avoid drug—drug interactions.

Building medication reconciliation into your practice using the following simplified process is a great way to prevent errors and potential adverse events4,5:

- Request a current list of medications during registration.Ask specifically about prescriptions, OTC medications, vitamins/minerals, and supplements.Include different dose forms: creams, eye drops, and inhalers.Note drug name, dose, frequency, and route.

- Compare the list with the patient profile and review it with the patient.If your records are discordant, ask patients if they:See multiple prescribersRecently had a change to their medicationsUse multiple pharmacies or receive mail-order medications

- Provide this medication list to the patient and primary care provider.Ensure that the patient understands the role of each medication in their health care regimen.Provide education as needed.

- Explain the importance of maintaining an accurate medication list.

Drug—DrugInteractions

Drugs can interact with each other pharmacodynamically or pharmacokinetically. Pharmacodynamic interactions involve what the body does to the drug, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (the ADME principle). Pharmacokinetic interactions involve how the drug affects the body. Either type of interaction can lead to a drug’s being less effective, having unexpected and potentially dangerous adverse effects, or having increased drug action.6

The liver is critical for many drugs’ metabolism and excretion. Hepatocytes contain many enzymes that metabolize different chemicals. Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes are the most important, as many medications are CYP450 substrates.

Think about drug interactions in 4 ways7:

- Inhibition of metabolism.A CYP450 enzyme can be blocked by a medication. Drug elimination slows down due to enzyme inactivity, and drug levels increase.

- Induction of metabolism.The presence of a drug causes increased CYP450 enzyme production. It increases drug metabolism, and drug levels decrease.

- Inhibition of excretion.The inhibition of certain excretion pathways in the kidney can increase drug levels.

- Synergism.When 2 medications are taken together and the effect of one, or both, is increased, causing enhanced therapeutic or adverse effects.

High-Risk AntidiabeticDrug—DrugCombinations

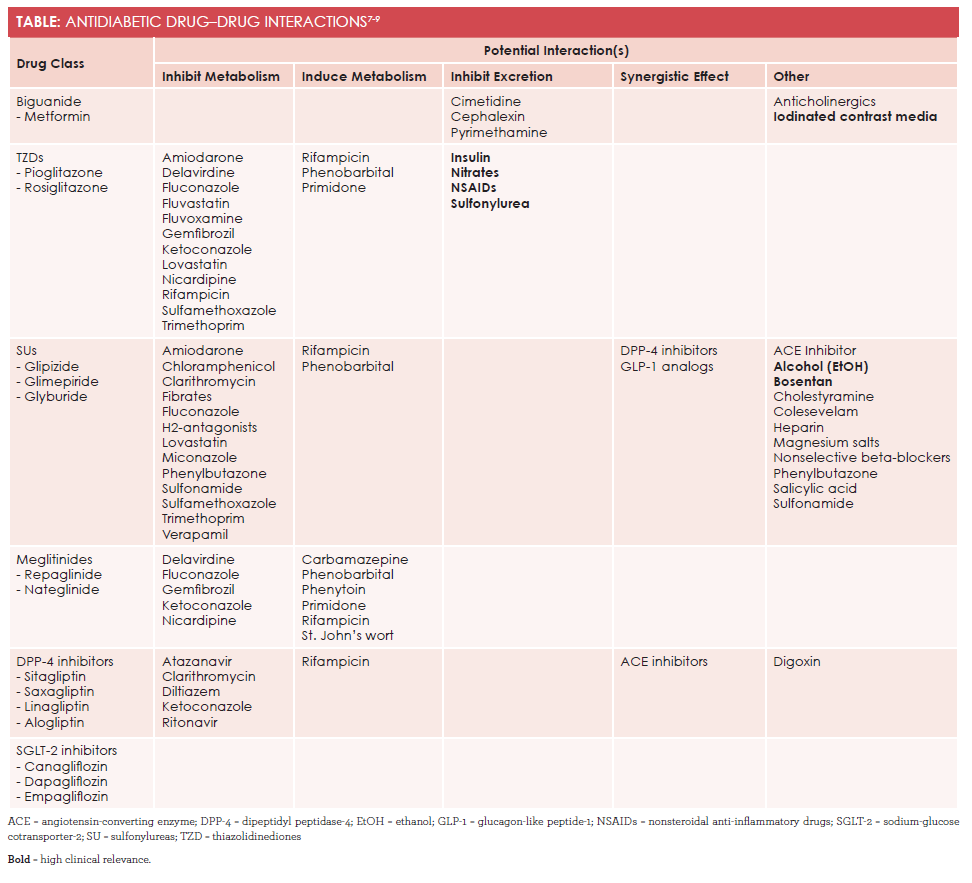

Relevant drug­—drug combinations and the mechanism of interaction are summarized in theTable.7-9Many clinically relevant drug interactions are based on the drug’s effect on specific CYP50 enzymes. Thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, and meglitinides are the most susceptible to these types of interactions in the following ways:8

- Thiazolidinediones can have a potentially synergistic effect when given with insulin, nitrates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or sulfonylurea.

- Excess alcohol consumption with sulfonylureas inhibits gluconeogenesis, which can cause prolonged hypoglycemia. The medication bosentan is contraindicated with sulfonylureas due to increased hepatotoxicity.

- Metformin has a low interaction risk, but a major risk is coadministration with iodinated contrast media. Patients must stop metformin 48 hours before a procedure, and wait 48 hours after the procedure to resume.

With the exception of saxagliptin, dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors also show a very low interaction potential. Specifically, saxagliptin is affected by CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers. On the other hand, giving DPP-4 inhibitors with drugs that affect the drug transporter P-glycoprotein might affect plasma levels.

P-glycoprotein has a wide substrate spectrum. It is involved in the transport of drugs from different drug classes including antineoplastic drugs (eg, docetaxel, etoposide, vincristine), calcium channel blockers, calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus), digoxin, macrolide antibiotics (eg, clarithromycin), and protease inhibitors.8

A newer antidiabetic drug class, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, has a very low risk of drug interactions.8

Conclusion

Antidiabetic drugs have numerous interactions. A good practice is to use a drug­—drug interaction checker if any questions arise. Several are available online, and pharmacists can scan medication profiles quickly for interactions (and are happy to do so). Quality care starts with the clinician obtaining a complete medication list for each patient at the start of each visit.

Lauren Trahan is a PharmD candidate at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

References

- CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. CDC website. cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2016.

- Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care.Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725-731.

- Leichter SB, Faulkner S, Camp J. On the cost of being a diabetic patient: variables for physician prescribing behavior.Clin Diabetes. 2000;18(1):42-44. journal.diabetes.org/clinicaldiabetes/v18n12000/pg42.htm. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- The National Learning Consortium. Medication Reconciliation Meaningful Use Toolkit. healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/medication-reconciliation-meaningful-use-toolkit.docx. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- Singh H, Sittig DF, Layden M. Reconciling Records. US Department of Health and Human Services website. psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/229/reconciling-records. Published November 2010. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- FDA. Drug interactions: what you should know. FDA website. fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/ucm163354.htm. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- Marino MT. Dangerous drug combinations. Diabetes Self-Management website. diabetesselfmanagement.com/managing-diabetes/treatment-approaches/dangerous-drug-combinations/. Accessed June 22, 2016.8.

- May M, Schindler C. Clinically and pharmacologically relevant interactions of antidiabetic drugs.Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2016;7(2):69-83. doi: 10.1177/2042018816638050.

- Triplitt C. Drug interactions of medications commonly used in diabetes.DiabetesSpectr. 2006;19(4):202-211.