Atypical Symptoms of Myocardial Infarction Associated with Coronary Risk Factors

Despite a remarkable decline in deaths due to cardiovascular disease over several decades, coronary heart disease remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States.

Introduction

Despite a remarkable decline in deaths due to cardiovascular disease over several decades, coronary heart disease (CHD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States.1More than 370,000 Americans die of CHD each year, and about 47% have at least one of the 3 key risk factors for CHD: high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.2Myocardial infarction (MI) remains the most common complication of CHD. An estimated 735,000 Americans experience an MI each year.2

Among all age groups, CHD mortality rates fell as much as 52% in men and 49% in women between 1980 and 2002.3However, these trends have not been seen across all demographic groups. Specifically, there was a dramatic slowing in the average annual rate of decline of CHD mortality among younger females between 35-54 years of age.3Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys show that the prevalence of MI has increased in women aged 35 to 54 years and declined in similarly aged men.4Women, continue to show much slower reductions in CHD mortality, bordering on stagnation.3In the last decade, the observed decline reflects mainly CHD mortality reductions among older adults.3

The following sequence of events commonly occurs with an MI5:

- Sudden disruption of an atheromatous plaque by intraplaque hemorrhage or mechanical force leads to the exposure of subendothelial collagen and necrotic plaque contents to the bloodstream.

- When platelets adhere, they release thromboxane A2, adenosine diphosphate, and serotonin, which cause additional platelet aggregation and vasospasm.

- Coagulation adds to a growing thrombus.

- The thrombus may completely occlude the coronary artery lumen in a matter of minutes.

The relative contribution of various processes leading to ischemia differs markedly between genders: women with ischemic heart disease have obstructive and extensive epicardial artery disease less frequently than men5; this implies that in women, other mechanisms—such as abnormal coronary vasomotion, nonatherosclerotic coronary artery dissection, impaired coronary microcirculation, thrombophilia, or as yet unknown processes contribute to ischemic syndromes more frequently than in men.6-9

Common symptoms of MI include10:

- Chest pain that does not go away with rest or that worsens with a deep breath

- Shortness of breath

- Pain or discomfort that radiates to arms or to the jaw

- Nausea and vomiting

Diaphoresis

Common symptoms of MI are apparent to health care providers. But, too often, patients who are experiencing the typical signs of MI may or may not recognize these episodes as an emergency and may not seek help immediately.11Patients who experience atypical symptoms, have an even greater risk of neglecting to seek emergency care.8Recent evidence suggests that in patients with CHD, 70% to 80% of episodes of ischemia are actually asymptomatic.9Three factors most likely account for the large proportion of asymptomatic episodes include dysfunction of afferent nerves, transient reduced perfusion, and differing pain thresholds among patients.10

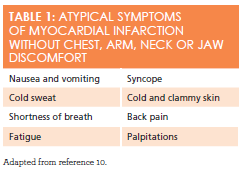

Patients who do not experience chest pain on presentation to the hospital represent a large portion of the MI population and are at increased risk for delays in seeking medical attention, less aggressive treatments, and in-hospital mortality.12Symptoms that are not usually associated with an MI are listed inTable 1.9,10One study found that one in 3 patients diagnosed as having MI on admission did not have chest pain on presentation. Contrary to popular thought, patients with diabetes make up less than onethird of this group.12Although diabetes is an important risk factor for atypical presentation, other risk factors associated with the absence of chest pain include older age, female sex, nonwhite racial/ethnic group, and a prior history of congestive heart failure and stroke.12

It is disconcerting that patients with atypical presentation may seek medical attention in primary care settings rather than at emergency departments. It is important for health care providers who work in primary care and retail health clinics to identify both typical and atypical symptoms of MI to avoid a delay in diagnosis and recommended therapy11. Although retail health clinics direct their care toward treating minor acute illness, patients can present in these clinical setting with very serious health problems such as an acute MI. The objective of this case study is to discuss an example of a 52-yearold woman presenting to a primary care clinic without chest pain but at increased risk for an MI, whose symptoms may not be apparent to patients and health care providers.

History

SB is a 52-year-old woman who presents for the first time with new onset fatigue and shortness of breath. She lost her full time job 3 months ago and has been considering options to go back to school for a certified nursing assistant certificate. Over the past 2 weeks, SB has noted that when she walks to the bus to get to school, she feels more tired and short of breath. She has been gaining weight since she lost her job and feels that this is due to her decreased activity. She denies chest pain, productive cough, and upper respiratory infection symptoms. She has tried walking slower, which eases the symptoms, but she still feels very tired. She has been taking her medications for hypertension but is running out and needs a new prescription. She was taking hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg once daily and is now taking amlodipine 10 mg once daily. She misses about 1 or 2 doses per month.

DISCUSSION QUESTION:What additional information would you want to know about SB’s history and current illness?

ANSWER:A patient’s medical history and knowledge of risk factors for MI are critical to an accurate diagnosis. You decide that you need a more detailed medical history from SB and proceed to ask her additional questions that elicit the following information:

REVIEW OF SYMPTOMS:SB states that her overall health has been good during the past 12 months, though today she is feeling extremely tired. Her weight has increased approximately 20 pounds during the past year. This weight gain represents nearly a 12% increase in total body weight. She reports some shortness of breath with activity, especially when climbing stairs, and that her breathing difficulties are getting worse. She sleeps on 2 pillows but denies paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. She denies shortness of breath at rest, headaches, nocturia, nosebleeds, hemoptysis, asthma, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blood in the stool, genitourinary symptoms, or a history of diabetes. She self-treats occasional bilateral knee pain with OTC extra-strength acetaminophen. She does not know her cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, or high-density lipoprotein levels.

PREVIOUS MEDICAL HISTORY:Hypertension was diagnosed at age 45 years, and it is not always in optimal control. SB is postmenopausal, having had her last menstrual period at age 50. She had pneumonia 6 years ago that resolved with antibiotic use. Her fallopian tube was removed 20 years ago after an ectopic pregnancy.

ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY:SB lives with an adult son with a severe learning disability. She rents an apartment in the inner city and is worried about making payments and paying for heating costs, as the winter months are approaching. She takes the bus, which is about 6 blocks from her home. There are many abandoned row homes in her community, but feels that she is safe to walk to the bus during the day. No one smokes in the house.

FAMILY HISTORY:SB’s father died of a heroin overdose at age 35 years. Her mother has type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Her grandparents are all dead; she does not know their causes of death, but reports that they were all older than 60 years. Her siblings and 3 children are alive and well.

SOCIAL HISTORY:SB divorced 20 years ago. She has worked as a teacher’s aide for the past 20 years, but she was laid off after the job description changed. She has never smoked, but her son smokes outside of the house. She drinks alcohol only on special occasions, fewer than 4 times a year, and may have 1 glass of wine. She knows she should cut down on salt but admits to eating high-sodium foods. She uses Mrs. Dash when cooking instead of table salt. She admits to snacking at night and has had difficulty sleeping. She does not fall asleep until 1 am or 2 am and gets up at 7 am every morning. She does not pay attention to the fat or carbohydrate content of the food that she eats. She has never dieted. Her only exercise is her walk to the bus Monday through Friday. She has never used street drugs.

DISCUSSION QUESTION:What is your initial impression of SB’s presentation?

ANSWER:Based on her history and risk factors, you are concerned that SB may have unstable angina and a possible MI. You know that one-third of patients who turn out to have had an MI present without chest pain on initial evaluation. Her other risk factors are that she is female and has a history of hypertension. You then move on to SB’s physical exam and find the following:

PHYSICAL EXAM:SB is an alert and oriented woman who looks to be her stated age. She is anxious and does not appear in acute distress. Skin is cool and diaphoretic, without cyanosis.

VITAL SIGNS:Height is 5’6”, weight is 190 lb, waist circumference is 36 in, body mass index is 30.6 kg/m2, pulse is 100 beats per minute (with an occasional premature beat), respiratory rate is 18 breaths per minute, temperature is 98.1°F, blood pressure is 160/98 mm Hg.

NECK:Supple without thyromegaly, adenopathy, bruits, or jugular venous distention.

HEAD, EYES, EARS, NOSE, AND THROAT:Pupils are equal, round, and react to light and accommodation. Extraocular movement is intact, fundi are benign, and tympanic membranes are intact. Pharynx is clear.

CHEST:No tenderness with palpation of chest wall. No dullness on percussion. Bilateral breath sounds are clear to auscultation. Slight bibasilar inspiratory crackles with auscultation. No wheezes or friction rubs.

HEART:Tachycardia is noted, with occasional premature beat. Normal first and second heart sounds. No third heart sound is heard. Fourth heart sound is soft. No murmurs or rubs are heard.

ABDOMEN:Soft and nontender, negative for bruits and organomegaly, bowel sounds heard throughout.

MUSCULOSKELETAL/EXTREMITIES:Normal range of motion throughout, muscle strength 5/5 in upper and lower extremities, bilaterally. Pulses are 2+; no bruits; 1+ edema from ankle to mid-calf on left and right.

NEUROLOGICAL:Cranial nerves II through XII are intact. Cognition, sensation, gait, and deep tendon reflexes are within normal limits. Babinski reflex is negative.

OTHER DIAGNOSTICS:

- 12-LEAD ELECTROCARDIOGRAM (ECG):4 mm ST segment elevation in leads V2through V6

- CHEST X-RAY:Bilateral mild pulmonary edema (<10% of lung fields) without pleural disease or widening of the mediastinum

- LABORATORY BLOOD TEST:SeeTable 2.

Table 2:Laboratory Blood Test Results with Normal Ranges13

Sodium 133 mEq/L

(135-145 mEq/L)

Magnesium 1.9 mg/dL

(1.8-3.0 mg/dL )

Creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB) 6.3 IU/L

(<16 IU/L)

Potassium 4.3 mEq/L

(3.5-5.0 mEq/L)

Phosphorus 2.3 mg/dL

(2.5-4.5 mg/dL )

Troponin I 0.3 ng/mL

(<0.05ng/mL)

Chloride 101 mEq/L

(101-112 mEq/L)

Total cholesterol 213 mg/dL

(<200 mg/dL)

Hemoglobin 13.9 g/dL

(12.0-15.5 g/dL, women)

Bicarbonate 22 mEq/L

(22-32 mEq/L)

Triglicerides 174 mg/dL

(<165 mg/dL)

Hematocrit 39%

(39-45%, women)

Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL

(8-20 mg/dL)

Low-density lipoproteins 143 mg/dL

(<130 mg/dL)

White blood count 4900/mm3(4,800-10,800/mm3)

Creatinine 0.9 mg/dL

(0.6-1.2 mg/dL)

High-density lipoproteins 32 mg/dL

(>40 mg/dL)

Platelet 267,000/mm3

(150, 000-450,000/mm3)

Glucose, fasting 200 mg/dL

(60-110 mg/dL)

Creatinine phosphokinase 99 IU/L (32-267 IU/L)

Glycated hemoglobin, HbA1c5.7% (3.9-6.9%)

DIAGNOSIS:ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). STEMI is suspected when a patient presents with persistent ST-segment elevation in 2 or more anatomically contiguous ECG leads in the context of a consistent clinical history.11CK-MB and cardiac-specific troponins confirm diagnosis, however, treatment should be started immediately in patients with a typical history and ECG changes, without waiting for laboratory results.

DISCUSSION QUESTION:What would you recommend and/or prescribe for SB’s treatment plan?

ANSWER:Based on her history and risk factors, you initially suspect new-onset atypical angina and want to rule out an MI. You review your institution-specific, guideline-based protocols for triaging and managing patients who present with symptoms that are suggestive of myocardial ischemia.

Treatment:11,14

- Dial 911, request emergency medical services (EMS) for an acute ST elevation MI.

- Request EMS to transfer patient to a percutaneous coronary intervention capable hospital because immediate and prompt revascularization can prevent or decrease myocardial damage and decrease morbidity and mortality.

- Apply supplemental O2.

- Instruct patient to chew 162 to 325mg of non-enteric coated Aspirin and 300mg of clopidogrel immediately (if aspirin is contraindicated, give clopidogrel 300mg, or prasug-rel 60mg only).

- Pain is treated with morphine sulfate IV 2-5mg Q5-30 min, if peripheral intravenous ac-cess is established.

- Give nitroglycerin 0.3-0.6 mg sublingual immediately, then repeat Q5 minutes, maximum 3 doses within 15 minutes.

- Maintain continuous 12-lead electrocardiogram monitoring until EMS arrives.

- Contact designated emergency contact for the patient.

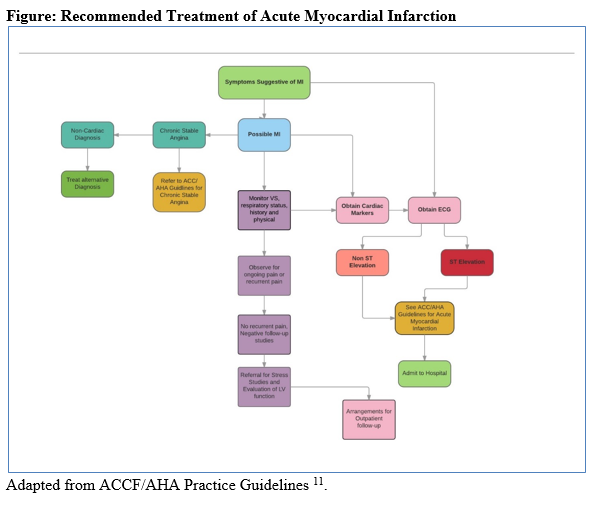

The American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) have jointly produced evidence-based guidelines for treating cardiovascular diseases for more than 3 decades.11These ACCF/ AHA practice guidelines assist clinicians in selecting the most effective strategies for treating individuals presenting with STEMI and other cardiovascular- related problems. The guidelines for treating individuals with symptoms that are suggestive of MI (seeFigure11) focus on taking a number of steps toward relieving symptoms, implementing diagnostics, and prescribing appropriate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions to manage the symptoms of MI.11It is important for providers to refer to the practice guidelines as they are intended to assist with clinical decision-making, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of specific cardiovascular-related problems.

Conclusion

This case study presents one example of a common health disparity among women who present with atypical symptoms of MI associated with the common risk factors for CHD. Common risk factors for SB includes obesity, hypertension, stress, pre-diabetes, hyperlipidemia, sedentary life-style, insomnia, and the inability to adhere to prescribed medication regimen due to financial constraints. In light of these significant risk factors for CHD, the primary care provider needs to have a heightened awareness of atypical symptoms representing an MI.

Most cases of MI are associated with typical symptoms such as chest pain and shortness of breath. However, there is a large proportion of patients who present with symptoms not typically associated with an MI. Atypical presentation of MI is most commonly seen in individuals older than 75 years and in women.11,12Patients who present with atypical symptoms often experience delays in treatment, which can lead to additional complications and poor health outcomes.11,12

It is important that health care providers identify symptoms, provide initial treatment, and make appropriate recommendations based on their institutional and ACCF/AHA practice guidelines.11For cases with atypical representation, health care providers must apply the same treatment protocols for any case of MI. Education is key to helping patients identify symptoms of MI, whether typical or atypical.

Mary Donnelly-Strozzo, DNP, MPH, FNAP, ACNPBC, ANP-BC, is a nurse practitioner specializing in cardiovascular prevention and primary care. Her 44-year nursing career has been devoted to assesssing, treating, and planning care for adults. She currently teaches in the master’s nursing programs at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland.Diana Baptiste, DNP, MSN, RN, is a registered nurse specializing in cardiovascular prevention and health care who has had a 15-year nursing career devoted to caring for adults. She current-ly teaches across all levels of pre-licensure nursing programs at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. She has presented nationally and internationally on heart failure and nursing education, with a focus on promoting clinician competencies in acute care settings.

References

- Miniño AM, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD.National Vital Statistics Report..Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. DHHS publication 2012-1250. cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_10.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease facts. cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm. Accessed October 21, 2015

- Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the US from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2128-2132.

- Towfighi A, Zheng L, Ovbiagele B. Sex-specific trends in midlife coronary heart disease risk and prevalence. Arch. Intern. Med., 169; 2009:1762—1766.

- Kumar V, Abas AK, Aster JC. Heart: Ischemic heart disease In: Mitchell, RN, ed.Robbins Basic Pathology. eds. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2013: 377-382.

- Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with ‘‘normal’’ coronary arteries: a changing philosophy.JAMA. 2005;293(4):477-484

- Andreotti FN, Marchese F. Women and coronary disease.Heart. 2008;94(1):108-116.

- Ahmed AH, Shankar KJ, Eftekhari H, Munir MS, Robertson J, Brewer A, Stupin I, Ward Casscells s. Silent myocardial ischemia: current perspectives and future direction.Exp Clin Cardiol.2007; 12(4): 189-196.

- Jacobs, AK. Coronary intervention in 2009: are women no different than men? Circ Cardiovasc Interv.2009;2(1):69-78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.847954.

- McPhee SJ, Hammer GD. Cardiovascular disorders: Heart diseases. In: Kusumoto FM.Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010: 256-281

- O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circ. 2013;127(4):e362-425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6.

- Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain.JAMA.2000;283(24):3223-3229. doi:10.1001/jama.283.24.3223.

- Bruyere HJ. Appendix A. Table of clinical reference values.100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology.Philadelphia, PA. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009: 486-489.

- Eprocrates. ST-elevation myocardial infarction. https://online.epocrates.com/diseases/150/ST-elevation-myocardial-infarction. Accessed November 24, 2015.