PPIs and Antacids: How to Avoid Interactions

The introduction of proton pump inhibitors in the late 1980s dramatically changed the treatment and outcome of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in the late 1980s dramatically changed the treatment and outcome of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Commonly prescribed PPIs include omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex), dexlansoprazole (Dexilant), and esomeprazole (Nexium). Because billions of dollars are spent on PPIs each year in the United States, it is important for retail clinicians to know how to use them correctly.

PPIs are appropriate for most stomach acid—related pathologies. The onset of action of PPIs is much longer than the 1-hour onset of H2-receptor antagonists, such as famotidine (Pepcid).1,2On the other hand, neither PPIs nor H2blockers work as quickly as antacids such as Rolaids or Tums. There are certain situations and reasons for taking each category of these medications, and each has different contraindications and interactions, as well.

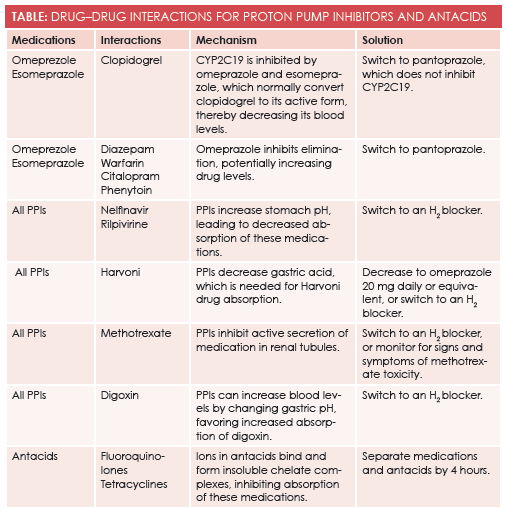

Omeprazole and other PPIs inhibit the CYP2C19 enzyme, which is a pathway for many medications. One medication metabolized into its active form through this pathway is clopidogrel (Plavix), a very commonly used antiplatelet agent.3The FDA issued a strong warning against using omeprazole and esomeprazole with clopidogrel because of the potentially decreased effectiveness for clopidogrel. A different PPI with weaker CYP2C19 inhibition, such as pantoprazole, should be used instead.3,4Other medications metabolized by the CYP2C19 enzyme pathway include diazepam, warfarin, citalopram, and phenytoin—all of which show increased serum levels with concomitant use of PPIs.

PPIs have the potential to interact with a wide variety of medications due to alteration of the pH of the stomach, which can potentially change absorption, activation, and binding of medications. Multiple HIV medications such as nelfinavir (Aricept) and rilpivirine (Edurant) require acid for proper absorption, so they are not absorbed in therapeutic doses when given with PPIs.5,6For the same reason, some hepatitis C medications require that lower-dose or no PPIs be given during therapy.7Conversely, PPIs will increase digoxin (Lanoxin) levels in the blood because of increased absorption, potentially leading to digoxin toxicity.8

Debate about whether PPIs alter absorption of vitamins and minerals has been ongoing for many years. Longterm treatment with a PPI decreases absorption of vitamin B12and iron, potentially leading to anemia, neurologic dysfunction, and other long-term complications.9Absorption of calcium and magnesium is also altered, and a systematic review of some studies has shown that long-term use of PPIs leads to increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly; however, the same systematic review of further studies failed to show correlation between osteoporosis and PPIs.9Nevertheless, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans are now being considered by some providers for patients who are on chronic PPI therapy.

Potential Effects on Gastrointestinal Health

PPIs not only affect oral medications in a variety of ways, they also alter gut flora by increasing the pH of the stomach, allowing ingested bacteria to survive the usual harsh acid environment. Results of many studies have shown a correlation between the use of PPIs and increased incidence of nosocomial and community-acquired pneumonia, as well asClostridium difficileinfection, especially when PPIs are co-administered with antibiotics.10-12Results from a recent study linked PPI use with small bowel intestinal overgrowth, which can lead to bloating, diarrhea, or abdominal discomfort.13

Antacids are not without drug interactions. Not only do they change the pH of the stomach transiently, they also add different multivalent ions to which medications can bind. Fluoroquinolones and tetracycline are well known to bind to these ions, forming insoluble chelate complexes that inhibit their absorption. Bisphosphonates are also known to bind via a similar mechanism, inhibiting their absorption, as well. One option is to space antacids 4 hours apart from medications that can be altered, given that the stomach normally clears antacids in this time frame.14

PPIs and antacids are not benign. Multiple drug interactions and adverse effects need to be considered when prescribing these medications (Table). Retail clinicians should have a careful plan to manage patients on PPIs and antacids, and patients should be monitored at every clinic visit to determine whether the medication should be continued. PPIs and antacids truly are wonderful medications when used correctly.

Lois Obert is a nurse practitioner with a doctorate in nursing practice from the University of Alabama. She works as a market educator in retail health for Take Care Health Systems. Her nurse practitioner background is primarily in education, leadership, and curriculum development.Jonathan Obert is a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, and nutrition fellow at the University of Louisville Department of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

References

- Drepper, M, Spahr, L, Frossard, JL. Clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors-where do we stand in 2012?World J Gastroenterol. 2012 May 14;18(18):2161-71.doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2161.

- http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm225843.htm. FDA website to show actual FDA warning for clopedigril and omeprazole.

- Vinay K, Abul A,Nelson F, Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease.7thed. Elsevier Inc. 810-875, 2005.

- Abe Y, Inamori M, Togawa J, et al. The comparative effects of single intravenous doses of omeprazole and famotidine on intragastric pH.J Gastroenterol. 2004 Jan;39(1):21-5.

- Lida H, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Early effects of intravenous administrations of lansoprazole and famotidine on intragastric pH.Hepatogastroenterology.2009 Mar-Apr;56(90): 551-4.

- Putcharoen O, Kerr S, Ruxrungtham K. An update on clinical utility of rilpivirine in the management of HIV infection in treatment-naïve patients.HIV AIDS (Auckl).2013 Sept 16;5:231-41.doi:10.2147/HIV.S25712.

- Lewis J, Stott K, Monnery D, et al. Managing potential drug-drug interactions between gastric acid-reducing agents and antiretroviral therapy: experience from a large HIV-positive cohort.Int J STD AIDS. 2015 Feb. 25. pii:0956462415574632.

- Diana G, Gregory H. Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir (Harvoni): Improving options for hepatitis C virus infection. P T. 2015 Apr; 40(4): 256-259.

- Oosterhuis B, Jonkman J, Anderson T, et al. Minor effect of multiple dose omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin after a single oral dose.Br J ClinPharmacol. 1991 Nov; 32(5): 569-572. PMCID:PMC1368632.

- Tetsuhide I, Robert J. Association of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy with bone fractures and effects on absorption of calcium, vitamin B12, iron, and magnesium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 Dec; 12(6): 448-457. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0141-0 PMCID: PMC2974811 NIHMSID: NIHMS239233.

- Emmae N, Ramsay, Nicole L, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of pneumonia: a comparison of cohort and self-controlled case series designs.BMCMed Res Methodol. 2013; 13:82. Published online 2013 Jun 24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-82.

- Roughead E, Ramsay E, Pratt N, Ryan P, Gilbert A. Proton-pump inhibitors and the risk of antibiotic use and hospitalization for pneumonia. Med J Aust. 2009 Feb 2;190(3):114-6.

- Jimenez A, Drees M, Loveridge-Lenza B, et al. TI exposure to gastric acid-suppression therapy is associated with health care-and community-associated clostridium difficile infection in children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Aug;61(2):208-11.

- Fujiwara Y, Watanabe T, Muraki M, et al. Association between chronic use of proton pump inhibitors and small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth assessed using lactulose hydrogen breath tests.Hepatogastroenterology. 2015 Mar-Apr;62(138):268-72.

- Ogawa R, Echizen H. Clinically significant drug interactions with antacids: an update. Drugs. 2011 Oct 1;71(14):1839-64. Published online 2013 Jun 24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-82.