Retail Clinicians: Pivotal Players in Cardiovascular Disease Treatment

Multiple factors make provision of cardiovascular disease treatment in retail health clinics a helpful treatment option for all but the most critical patients.

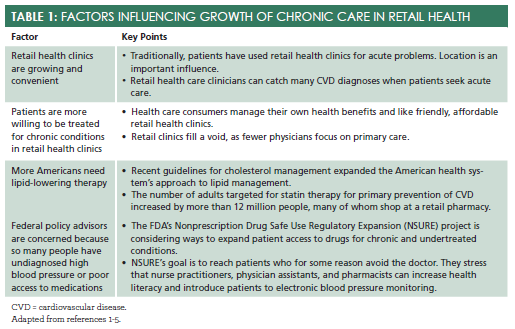

Multiple factors make provision of cardiovascular disease (CVD) treatment in retail health clinics a helpful treatment option for all but the most critical patients (seeTable 11-5). The roughly 10 million newly Obamacare-insured Americans need ready access to clinicians to guide them into the system and help them overcome the behaviors that were barriers to obtaining care in the past. Retail health care providers can encourage them to obtain preventive care, connect with physicians or specialists if necessary, and avoid the emergency department (ED) for routine care. This article outlines the steps for successful CVD management in retail health clinics.

Employ Evidence to Excel

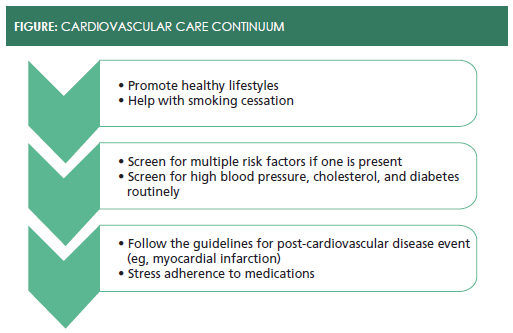

Expanding from episodic treatment to chronic CVD management as a national service strategy for your chain or a local initiative to engage underserved populations requires a specific skill set. Cardiovascular care occurs on a continuum (seeFigure). It begins with screening for the basic indicators. Collecting and documenting the following information from the patient is critical: sex, age, blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, smoking, level of physical activity, and cardiovascular risk. Counseling about lifestyle often helps patients make small changes that have profound impact on cardiovascular health. Nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants have proven they are effective in this role.6,7

Counsel Patients Through Lifestyle Changes

Clinicians use 2 cognitive behavioral counseling techniques to help patients embrace lifestyle changes and reduce CVD risk factors: motivational interviewing and the transtheoretical model (TTM) of behavioral change.7Most patients express ambivalence over behavioral change because it requires redefining their beliefs about the behavior and its role in their lives. Interviewers who use motivational interviewing elicit and resolve the patient’s ambivalence toward behavioral change in a therapeutic and nonconfrontational way. This creates readiness to change. Clinicians adhere to the following 4 principles during interactions with patients:

- Express empathy (“I know this is hard...”)

- Develop discrepancies in the patient’s beliefs (“I see that you are concerned about your smoking but reluctant to quit...”)

- Roll with resistance (“This may not be the right time to lose weight with all that’s going on. When should we talk about this again?”), and

- Support self-efficacy (“Your success this month shows you can do it!”).8

Motivational interviewing is coaching. Effective clinicians focus on the patient’s perceptions and coach patients on how they can make personal choices to improve or correct problem behavior. They also elicit the patient’s concerns about the problem, and when they face denial, they reflect, repeating back what the patient says and gently pointing out discrepancies without arguing.

Obviously, motivational interviewing takes time—time you may not have—so experts advise using 1 or 2 questioning approaches at every visit.

TTM integrates various theories concerning interventions for behavioral change and stresses individual decision- making ability. TTM is built on research that shows behavior changes occur in stages. Most patients need to think about significant behavior changes (precontemplationandcontemplationstages). Thepreparationandactionstages follow. Once patients make a change they enter themaintenancestage, a lifelong skirmish of consolidating gains and resisting regression. The final stage istermination, a place patients may never reach if the struggle with temptation is lifelong.9Using this model, clinicians walk patients through change’s stages, using empathy and providing support.

Evidence-Based Cardiovascular Care

Lifestyle changes are always necessary, but often insufficient. When patients need treatment, the next step is to turn to established guidelines. The number of clinical practice guidelines has exploded in recent years, and they cover prevention, screening, treatment, and a range of topics in between. One benefit of membership in nurse practitioner and physician assistant professional organizations is that they often review, recommend, or provide preferred guidelines. Often, health care systems embed guideline recommendations within electronic medical record systems and mobile devices, making them accessible (and difficult to ignore). In cardiology, 2 guidelines comprise the gold standard for patient care (seeTable 210-11).

Promoting medication adherence, which improves outcomes and reduces total health care costs, is the principal focus of retail health care providers.12,13Patients’ adherence rates are notoriously low, hovering around 50%, even after they have had a life threatening event (eg, a heart attack) or when medication is free.14Physicians are often frustrated by the adherence dilemma, and feel they have no control of patient behavior outside the office. They often use lab tests as adherence markers and a tool to motivate patients to adhere to medication.15

Reliance on lab tests alone is ill-advised. Team-based, data-driven approaches improve patient adherence considerably more than physician- based interventions.16-18Americans visit retail locations far more often than they visit their physicians. Having convenient, community-based access to retail care providers ensures that patients are consistently reminded about adherence. Retail care providers can:

- offer point-of-care cholesterol testing,

- perform risk-stratification to determine whether statins are appropriate, and

- write prescriptions based on clinical guidelines for dosing and measurement.

Neighborhood-based health care has been proposed as the ideal way to improve health and reduce total health care costs. Communication among retail health clinicians, pharmacists, and primary care doctors will be critical.

Some patients experience white coat hypertension (WCH) in health care settings. Long considered harmless, recent studies indicate many patients with WCH often have unidentified elevated blood pressure at other times and develop CVD as they age.19 Monitoring at home reports accurate readings and shows which patients who have WCH are at elevated risk for later problems.

Providing Safe, Successful Cardiovascular Care

Retailers built their health care model around 20-minute visits, but acknowledge that chronic care visits may need to be longer. Many allow scheduled appointments during the slower (midday) times and lengthen appointments to 30 minutes.5

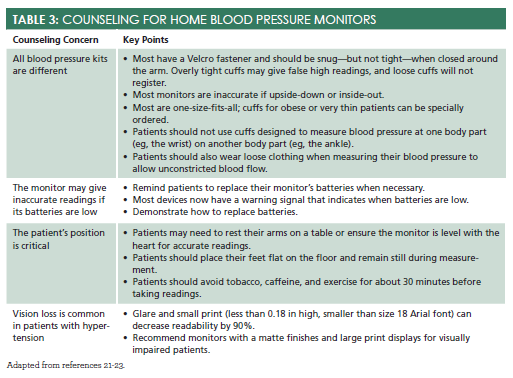

Home blood pressure monitors allow patients to track blood pressure in a familiar setting, determine if medication is working, and catch changes early.20Patients who select new blood pressure cuffs need counseling (seeTable 321-23).

Always advise patients to return for medication or a medication adjustment if blood pressure rises and stays high, or visit an ED if the results are very high. Also advise them to stay alert for falling blood pressure, especially if they are actively losing weight or quitting smoking. Consider making periodic phone calls to patients to check on their progress and encourage them.

Coordinating care and sharing information with the patient’s primary care medical home is important. Basic courtesies like notifying the patient’s primary care provider (PCP) that you’ve seen the patient and sending notes about what you found are a start. Communication can be facilitated using integrated electronic medical records, and increasingly, groups of providers are collaborating and sharing health information. Often, reluctant PCPs are convinced to connect electronically when they realize that team-based adherence strategies make care more accessible at lower cost and improve patients’ outcomes. They also appreciate referrals for more complicated cases.15

End Note

Retail health care is at an exciting point in its development. Retail pharmacies’ expansion into health care services could be a winning development for patients and providers. Retail prescribers who (1) actively educate patients and encourage patients to engage in chronic care, (2) use their electronic health records effectively, and (3) partner with area providers and assess quality routinely, are poised to benefit.

Ms. Wick is a visiting professor at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy.

References

- Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample.N Engl J Med.2014(15);370:1422-1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665.

- Rand Corporation. Retail health care clinics. www.rand.org/topics/retail-health-care-clinics.html. Accessed October 29, 2015.

- Rossi S. The doctor will see you in a minute: a study of the rising relevancy of retail clinics and its implications on traditional health systems. Lehigh Valley Health Network website. http://scholarlyworks.lvhn.org/research-scholars-posters/406/. Published July 31, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2015.

- Mehta RS. Nonprescription drug safe use regulatory expansion (NSURE). www.fda.gov/downloads/ForHealthProfessionals/UCM330650.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- Frieden J. Retail clinics branch into chronic disease treatment. Published March 25, 2010. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/HealthCare/retail-clinics-branch-chronic-disease-treatment/story?id=10152224. Published March 25, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- Klemenc-Ketis Z, Terbovc A, Gomiscek B, Kersnik J. Role of nurse practitioners in reducing cardiovascular risk factors: a retrospective cohort study.J Clin Nurs.2015;24(21-22):3077-3083.

- Farrell TC, Keeping-Burke L. The primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: nurse practitioners using behaviour modification strategies.Can J Cardiovasc Nurs.2014;24(1):8-15.

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler, CC.Motivational Interviewing in Healthcare: Helping Patients Change Behavior.New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change.Am J Health Promot. 1997:12(1):38-48. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Council.JAMA. 2014;311(5);507-520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 129(5 suppl):S1-S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a.

- Bitton A, Choudhry NK, Matlin OS, Swanton K, Shrank WH. The impact of medication adherence on coronary artery disease costs and outcomes: a systematic review.Am J Med. 2013;126(4):357.e7-357. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.09.004.

- Roebuck MC, Liberman JN, Gemmill-Toyama M, Brennan TA. Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending.Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(1):91-99. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1087.

- Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med.2011;365(22):2088-2097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913.

- Shrank WH, Sussman A, Brennan TA. The role of retail pharmacies in CVD prevention after the release of the ATP IV guidelines.Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(11):e487-e489. www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2014/2014-vol20-n11/the-role-of-retail-pharmacies-in-cvd-prevention-after-the-release-of-the-atp-iv-guidelines. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(6):540-550.

- Cutrona SL, Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, et al. Targeting cardiovascular medication adherence interventions.J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(3):381-397. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10211.

- Cutrona SL, Choudhry NK, Stedman M, et al. Physician effectiveness in interventions to improve cardiovascular medication adherence: a systematic review.J Gen Intern Med.2010;25(10):1090-1096. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1387-9.

- Cuspidi C, Rescaldani M, Tadic M, Sala C, Grassi G, Mancia G. White-coat hypertension, as defined by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, and subclinical cardiac organ damage: a meta-analysis.J Hypertens. 2014 Nov 6. [Epub ahead of print].

- Ross KL, Bhasin S, Wilson MP, Stewart SA, Wilson TW. Accuracy of drug store blood pressure monitors: an observational study.Blood Press Monit.2013;18(6):339-341. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000003.

- Braun Gmb. Braun Sensor Control Easy Click [owner’s manual].

- Omron Healthcare Co, Ltd. Omron blood pressure monitor [owner’s manual].

- Wallace LS, Keenum AJ. Using a home blood pressure monitor: do accompanying instructional materials meet low literacy guidelines?Blood Press Monit.2008;13(4):219-223. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283057b0a.